By Sunny Frothingham, Senior Researcher

Note: Thanks to ACLU-NC’s Emily Seawell and Rachel Geissler, and to Blueprint NC’s Dan DeRosa for their contributions to this research.

Over the last decade, North Carolina has become infamous for some of the nation’s most harmful voter suppression tactics — from racially-gerrymandered voting districts, to strict photo voter ID laws, to attacks on election safety nets, and, most recently, vote theft in North Carolina’s Ninth Congressional District. These attacks have also extended to Early Voting, the 17-day period before Election Day1 when the majority of North Carolina voters cast their ballots.2

A 2013 law dubbed the “Monster Voter Suppression Law” not only installed a strict photo ID requirement to vote, but also eliminated crucial reforms which expanded ballot access, including pre-registration for 16- and 17-year olds, out-of-precinct voting and same day registration, and shortened the Early Voting period by a week. Since 2016, when that law was overturned by the Fourth Circuit for “discriminatory intent” which “target[ed] African American voters with almost surgical precision,”3 the General Assembly has revisited, and in some cases revived, portions of the law, presumably in hopes of withstanding legal challenges. These efforts included placing a photo ID constitutional amendment on the ballot in November 2018 and passing Senate Bill 325 (S325), which had the impact of limiting Early Voting options in many parts of the state.

As explored below, S325 drained local resources and led counties across the state to reduce Early Voting sites and weekend voting options. In addition to S325’s onerous requirements on counties, the law also explicitly eliminated the last Saturday of Early Voting for all elections after 2018. Topline findings of the analysis include:

- After S325, 43 of North Carolina’s 100 counties eliminated at least one Early Voting site, almost half reduced the number of weekend days, and about two-thirds reduced the number of weekend hours, compared to 2014.

- While 2018 was a high turnout election statewide compared to 2014, site changes chipped away at county-level performance, especially in rural counties where the distance between voters and Early Voting sites increased the most.

- The last Saturday was the only weekend option in 56 of North Carolina’s 100 counties in 2018 — meaning that without it, there may be no weekend voting in more than half of North Carolina counties in future elections.

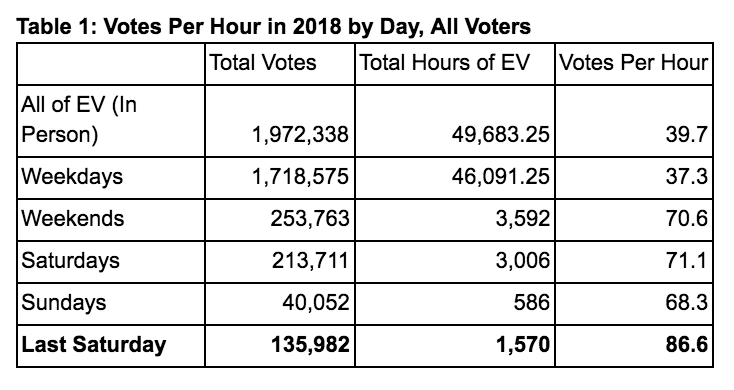

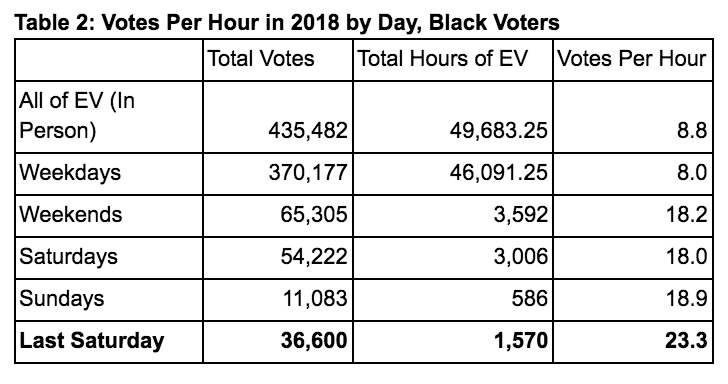

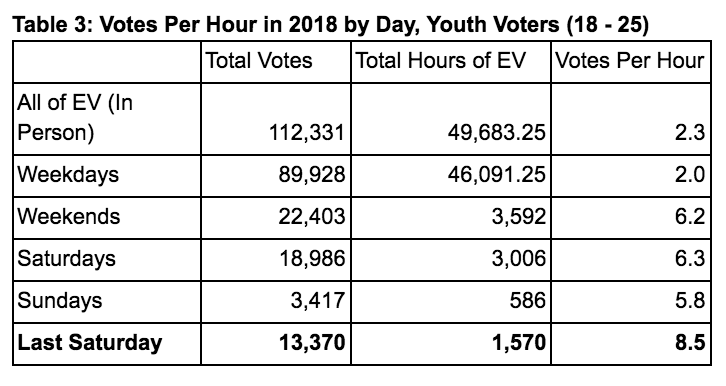

- The loss of the final Saturday will limit ballot access for voters across the state – more than two times the number of voters cast ballots, per hour, on the last Saturday compared to weekdays in 2018. The last Saturday garnered more than four times the 18- to 25-year old voters per hour than the weekday average.

- The elimination of the last Saturday will disproportionately harm young voters, Black voters, Latinx voters, and voters in certain rural counties.

Democracy North Carolina urges lawmakers to act now to ensure that all voters have a fair chance to cast their ballots in 2020. Lawmakers should:

- Give county boards of elections (BOEs) back the maximum flexibility needed to make the best decisions for their county’s resources and voters, as is available in current proposals like H893.

- If H893 is unable to garner the bipartisan support needed to pass, then lawmakers should eliminate the 7 a.m. – 7 p.m. weekday requirement, which requires county BOEs to operate during “non-usable” hours and limits the capacity of local Boards to operate multiple sites and provide weekend hours.

- At a minimum, lawmakers should restore the mandatory last Saturday for all future elections, including 2020.

Part One: Background on S325

In the summer of 2018, the General Assembly hastily enacted Senate Bill 325 (S325), the Uniform & Expanded Early Voting Act, which drastically reduced the discretion county BOEs have over designing Early Voting plans that work for their communities.4 North Carolina law requires counties to make Early Voting available at a minimum of one location (at the county Board of Elections office) and permits counties to establish additional sites throughout the county (referred to as satellite sites). In past cycles, counties were able to use their discretion about how best to allocate hours throughout the Early Voting window based on voter usage patterns5 — for instance, by staying open later on one weekday evening per week, opening mid-morning, or opening more satellite sites for the last two weeks of the Early Voting period. But S325 required all satellite sites to be open from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. every weekday and in operation for the entire Early Voting period. The bill originally proposed eliminating the extremely popular final Saturday in 2018 by moving the Early Voting period up a day, to start on a Wednesday instead of a Thursday and end on a Friday, instead of Saturday. Lawmakers added the last Saturday back for the 2018 election only after advocates spoke out in opposition. As the law currently stands, the final Saturday of Early Voting is eliminated for all future elections, including 2020,6 despite its popularity among North Carolina voters and disproportionate use by Black and Latinx voters.7

S325 Undermined Local Control Over Early Voting

S325 dramatically increased the cost to counties of having multiple Early Voting locations and made it harder to operate weekend options (other than the required last Saturday in 2018). During the debate on the bill and following its passage, county BOE members and staff expressed frustration about the new, top-down state mandate and the loss of flexibility in designing their county’s Early Voting schedules. As Viola Williams, Hyde County Director Of Elections put it, “I really wish, before the bill had even been pushed through, that they would have gotten the opinions of the people who are directly involved. The way things were done before, where the counties made the plans, was a better way to do it. Each county is going to make plans for what benefits their county the most, whereas when the state steps in, they try to benefit all counties. All counties are not the same.”8

Before S325, county boards could flexibly allocate hours across sites and prioritize staffing high-volume voting times. According to Adam Ragan, Director of Elections in Gaston County, in a media interview ahead of the 2018 election: “In elections administration, we have what we consider ‘non-usable hours,’ that’s why we’ve never opened sites that early.”9 In addition to the requirement that counties operate Early Voting during these “non-usable” hours, the new mandate made it impossible for some counties to keep popular satellite sites open. “I would have loved to have had more Early Voting locations,” Ragan said. “It came down to having more locations, helping more voters versus our fiduciary responsibilities to the county.10 Tony McQueen, the Deputy Director of Elections in Pitt County, echoed this point: “To run seven sites, for all of that time, would increase our budget by two-thirds… We’ve just been buffaloed, really.”11

At the county level, frustration with the law was bipartisan. Both Democratic and Republican members of the Bladen County Board of Elections lamented the impact of S325. Bladen could only afford one Early Voting site in 2018, compared to the four sites it operated in the 2012, 2014, and 2016 cycles. As Bobby Ledlum, the Republican County Board chair, shared with ProPublica at the time, “We’re a small county and the law has affected us pretty badly.” Al Daniels, a Democratic member, saw the law as “part of a larger voter suppression effort” and “anti-voter, period.”12 Steve Stone, Chair of the Robeson County Board of Elections, said before the election, “I’m a full-fledged Republican and a Republican supporter, and I’m just disappointed in the General Assembly for not reaching out to election officials in the state and asking, ‘What do you think would work well for this early voting law?’”13

Part Two: Effects of Eliminating Sites and Hours

The Law Led to the Elimination of Early Voting Sites and Hours

The uniform hours mandate imposed by S325 was a significant departure from the way county Boards of Elections had managed Early Voting schedules in the past. Roughly half of North Carolina’s counties used flexible scheduling during Early Voting in midterm cycles.14 In the 2018 Primary, 46 counties chose to offer varied hours or days at satellite sites (sites other than the required Board of Elections site)15 during Early Voting to make voting more cost-efficient based on when and where demand was highest. In 2014, the previous midterm election, 55 counties took advantage of the flexibility provided by the pre-S325 law.16

After S325, 43 counties reduced the number of Early Voting sites offered in 2018 compared to 2014, 47 counties reduced the number of weekend days offered (despite the fact that the 2018 Early Voting period included an additional weekend, since 2014’s Early Voting period was cut to 10 days), and 65 counties reduced the number of weekend hours.17

Figure 1: County by County Site and Weekend Day Reductions in 201818

2018 Figures Indicate a Relationship Between Early Voting Site Elimination and Turnout

Given the enthusiastic turnout of North Carolina voters in 2018, proponents of the law might attempt to dismiss the harmful impact of S325’s Early Voting restrictions. However, as Democracy North Carolina has noted in previous reports, turnout alone cannot fully reflect voter experience or voter access — by definition, it cannot quantify the number of people who did not vote due to election administration challenges, like long lines, poorly trained poll workers, or limited Early Voting sites and weekend hours.19 And while overall 2018 turnout was impressive for a midterm election, the data at the county level tells a different story. As seen below, turnout increased less in counties where Early Voting sites were farther away from voters. This effect was especially dramatic for North Carolina’s youngest voters, ages 18-25.

Ahead of the 2018 election, Propublica and WRAL teamed up to examine how S325’s changes to Early Voting sites impacted voters. Their analysis calculated the average change in distance, at the county level, between each voter and the closest Early Voting site. In most cases, the increases in distance resulted from site elimination, but it also happened in counties that changed Early Voting site locations.20 While driving a few additional miles might not be prohibitive to every voter, the added distance can be disenfranchising for many. For low-income voters and others with limited mobility or limited access to transportation, like seniors and people with disabilities, eliminating an Early Voting site can easily place voting out of reach — especially in rural counties where communities are more spread out and public transit options are slim to nonexistent.21

As seen in Figure 2 below, turnout increased less, compared to 2014, in counties where Early Voting sites were farther from voters. While statewide turnout jumped 9 percentage points from 44% in 2014 to 53% in 2018, that surge eroded in counties with fewer sites and significant increases in distance between polls. Between 2014 and 2018 counties saw almost a percentage point drop in the turnout margin for each added mile from voters to Early Voting sites.

The trend was even more extreme for 18- to 25-year olds, as seen in Figure 2. The turnout rate for North Carolina’s youngest voters jumped 11% statewide, but each additional mile between voters and Early Voting sites shrank that surge in youth voting by more than a percentage point. For instance, in Bertie County, where the distance between voters and Early Voting sites increased by an average of 5.6 miles, youth turnout increased by 3.5 percentage points compared to 2014 — paling in comparison to the statewide 11 percentage point jump.

Figure 2: Increased Distance from Early Voting Sites and Turnout Margin Compared to 201422

As noted in the analysis by Propublica and WRAL, some of the greatest impacts of site elimination fell on rural voters: about 1 in 5 rural voters saw the distance to their closest Early Voting site increase by more than a mile. In some counties, like Halifax, it was more dramatic. In Halifax, which can be found in the bottom right corner of Figure 2, the average distance between voters and Early Voting sites increased by 6.5 miles,23 and the turnout rate actually decreased compared to 2014.

Only three counties in North Carolina saw a decrease in the overall 2018 turnout rate (the percentage of registered voters who cast ballots) compared to 2014: Halifax, Jones, and Pamlico counties. All three decreased only slightly below 2014 levels. Jones and Pamlico only had one site each in 2014, and thus could not have eliminated any sites — but both were significantly affected by Hurricane Florence’s devastation.24 Halifax had three sites open in 2014, but only one site in 2018, and reduced weekend hours compared to 2014.25

In urban counties, where county budgets were generally better equipped to absorb the increased costs associated with S325 (resulting in smaller average changes in distance) and where voters were more likely to be able to access public transportation, the impact of S325 was not as extreme. Still, almost 1 in 10 urban voters saw the distance to Early Voting sites increase by more than a mile.26

The Law Led to the Reduction of Weekend Early Voting Options

In addition to the pressure S325 placed on counties to eliminate Early Voting sites, the law priced many counties out of being able to offer weekend options. Because counties had to staff any open sites from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. on weekdays, many could not afford to staff their historically popular weekend options. As discussed further below, S325 required counties to be open for part of the last Saturday before Election Day in 2018, but even with that requirement, 65 counties reduced the number of weekend voting hours, and 47 counties reduced the number of weekend days of Early Voting. The reduction of weekend days offered is especially notable since the 2018 period included another entire weekend, or two potential weekend days, compared to the truncated 2014 period. And, as seen with site elimination, the impact was felt more deeply in rural counties — 70% of North Carolina’s rural counties offered fewer weekend hours in 2018 than in 2014, as did 57% of suburban counties and one sixth of urban counties.27

Of the eight rural Eastern counties where a majority of registered voters are Black,28 four of them (Bertie, Northampton, Halifax, and Vance) reduced Early Voting sites, and all eight reduced the number of weekend hours during the Early Voting period. Seven of the eight reduced weekend days, and the eighth, Halifax, could not have reduced weekend days, since Halifax was only open on one weekend day in 2014, the last Saturday. None of the eight saw increases in sites or weekend options.

Without weekend Early Voting options, many voters are far less likely to be able to get to the polls. For voters who work multiple jobs, voters who have long commutes during the week, or voters who rely on friends or family for transportation, weekend hours may be the only chance to vote in person. With S325’s elimination of the last Saturday of Early Voting in all future elections, as discussed below, voters can expect weekend options to continue to shrink precipitously.

Part Three: Effects Directly From Eliminating the Last Saturday of Early Voting

Elimination of the last Saturday will harm young voters, rural voters, Black and Latinx voters

Starting in 2019, S325 also eliminates the popular final Saturday of Early Voting (the Saturday before Election Day) for all future elections.29 Prior to S325, the Saturday before Election Day was the only weekend day of Early Voting that counties were mandated to provide. This elimination is likely to result in the majority of North Carolina counties having no weekend Early Voting options, which are crucial for voters who work during the week — especially since Election Day is also a work day for most voters. Without the last Saturday requirement in 2018, 56 counties — a majority — would have had no weekend option for voters to cast their ballots. Some proponents of S325 have argued that being open the last Saturday before election day is unnecessarily burdensome for county boards, who then need to pivot from Early Voting to Election Day. However, as Derek Bowens, Director of Durham’s County Board of Elections, noted in an interview with Democracy North Carolina, “Ultimately, our job is to do everything we can to facilitate voting, and [the last Saturday] is something we’ve done historically — we’ve made it work, we’ll make it work.”

The last Saturday of Early Voting is consistently one of the highest traffic days of the Early Voting period, despite most counties only being open in the morning, instead of all day (see Tables 1-3 below). In 2018, the average rate of voting, over the course of the entire Early Voting period was 39.7 votes for every hour of Early Voting offered. The last Saturday netted over 135,000 votes, even though most counties were only open for a portion of the day, and thus garnered significantly higher traffic, at 86.6 votes per hour.30 As seen below, the last Saturday got more than double the voters per hour than weekdays in 2018, a pattern which held true for Black voters. Black voters also used Sunday options at a slightly higher rate than Saturday options, standing out from the statewide trend. For North Carolina’s youngest voters, the importance of the last Saturday was even more dramatic – more than four times as many young voters cast ballots per hour on the last Saturday than on weekdays in 2018.

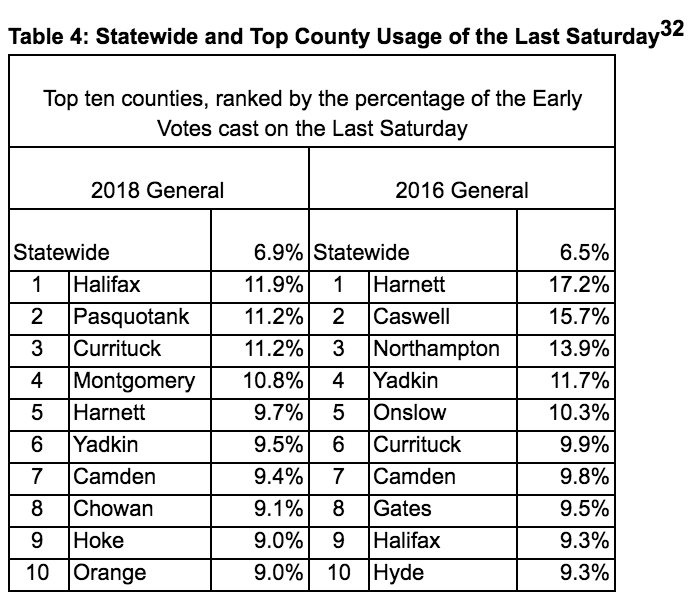

As with the lost Early Voting sites, rural voters will be significantly impacted by the elimination of the last Saturday. The top 10 counties with the heaviest usage of the last Saturday in 2016 were all rural counties, as were 9 of the top 10 in 2018.31 In the 2016 election, rural Harnett County, home of then-House Elections & Ethics Committee Co-Chair David Lewis, used the final Saturday of Early Voting at the highest rate in the state, with a stunning 17.2% of early voters in the county choosing to vote on the last Saturday (see Table 4 below).

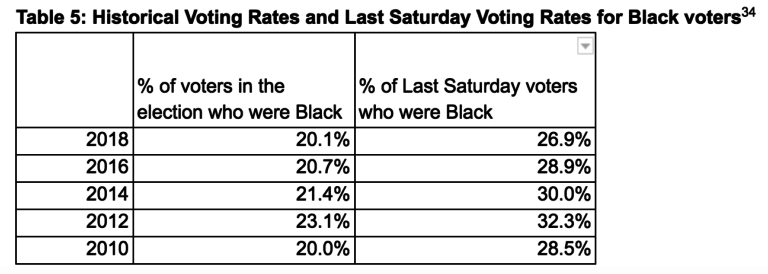

In addition to being popular among all voters and heavily used by rural voters in particular, the last Saturday of Early Voting has been disproportionately used by Black voters statewide (as seen in Table 5) in recent elections. In the 2016 General Election, Black voters made up 21% of those who voted in North Carolina, but 29% of those who cast ballots on the last Saturday. In the same election, Latinx voters disproportionately used the Last Saturday — making up 2% of voters, but 3% of those who cast ballots on the last Saturday.33

Conclusion and Recommendations

At best, S325 was a misguided attempt by the state to impose a one-size-fits-all structure on county Early Voting schedules, which historically varied widely from county to county to reflect the needs of North Carolina’s diverse voting populations. At worst, it was yet another cynical attempt to reduce voters’ access to Early Voting and Same Day Registration (available only during the Early Voting period), ahead of a critical midterm election. Regardless, the undisputed impact of the law was to reduce the number of Early Voting sites and weekend hours available to North Carolina voters and remove needed flexibility from those who are best positioned to understand what is needed for their voters — local Boards of Elections. Further, as shown by our analysis, those most impacted by these changes are rural North Carolinians, youth voters, and Black and Latinx voters.

Looking ahead to the 2020 election cycle including a fast-approaching March 3 Primary — when three times as many North Carolinians as in 2018 can be expected to cast their ballots — the constraints imposed by S325 will make it harder for voters to have their voices heard and for election officials to provide the robust Early Voting opportunities expected by North Carolina voters. Without a change, this major shift in Early Voting availability in a presidential cycle will predictably result in longer lines and more pressure on Election Day, and, in combination with the latest strict photo ID law going into effect, is especially likely to impact next year’s turnout. Now is the time for the North Carolina General Assembly to take proactive steps to show that it cares about the voices of all voters and to heed the bipartisan call of county election administrators to undo this misguided law.

In conclusion, Democracy North Carolina urges lawmakers to:

- Give county BOEs back the maximum flexibility needed to make the best decisions for counties’ resources and voters. House Bill 893 is one bill filed in the 2019-2020 legislative session that would do just that.35 H893 would change Early Voting law to pre-2013 flexibility, restoring the mandatory last Saturday of Early Voting (giving all North Carolina voters a weekend voting option), allowing counties the option to operate until 5 p.m. on that last Saturday, and providing maximum flexibility to county Boards of Elections to design and set Early Voting schedules that could vary across satellite sites. Currently, H893 does not have the bipartisan support needed to pass the Republican-dominated General Assembly.

- Eliminate the 7 a.m. – 7 p.m. weekday requirement, which requires county BOEs to operate during “non-usable” hours, and in practice limits the capacity of local Boards to operate multiple sites and provide weekend hours. H893 provides counties with the most ability to determine Early Voting schedules, based on their intimate knowledge of the county geography, population, and voters— but even a law that requires uniformity of hours for satellite sites, while not mandating an unnecessarily burdensome 12-hour weekday schedule, would be an improvement to the current law.

- Restore the mandatory last Saturday for 2020 and all future elections. While the best option would be one that frees county BOEs from Raleigh-imposed scheduling restrictions, restoration of the mandatory last Saturday for all future elections would at a minimum ensure that every county has at least one weekend voting option for working voters.

1 Under current law, the Early Voting period is 17 days – though it was truncated to only 10 days during the 2014 General Election and expanded to 18 days for the 2018 General Election.

2 Over 60% of ballots cast in the 2016 General Election were cast at Early Voting sites. Analysis by Democracy North Carolina, based on data available from the State Board of Elections as of April 2019. Data retrieved from https://dl.ncsbe.gov/?prefix=ENRS/.

3 N.C. St. Conf. of the NAACP v. McCrory, 831 F.3d 204, 219 (4th Cit. 2016). Retrieved from http://www.ca4.uscourts.gov/opinions/published/161468.p.pdf.

4 The Uniform & Expanded Early Voting Act, Session Law 2018-112, Senate Bill 325. Available at https://www.ncleg.gov/BillLookup/2017/S325. S325 as originally filed in the 2017-2018 legislative session had nothing to do with elections, but it emerged as the Uniform & Expanded Early Voting Act as a proposed committee substitute on June 14, 2018, and was ratified and sent to Governor Cooper just one day later. He vetoed the bill on June 25; the veto was overridden by the NCGA on June 27.

5 Prior to 2013, county Boards of Elections had maximum flexibility in deciding Early Voting schedules — no uniformity was required and counties could choose to operate until 5 p.m. on the last Saturday. In 2013, as part of Session Law 2013-381, H589, a sweeping elections omnibus dubbed the “Monster Voter Suppression Law” by voting rights advocates, county Boards were required to offer uniform hours at all satellite sites and voting was required to end by 1 p.m. on the last Saturday. This less onerous uniformity requirement was in effect for the 2014 and 2016 election cycles, as well as the 2018 Primary.

6 The Uniform & Expanded Early Voting Act, Session Law 2018-112, Senate Bill 325. Available at https://www.ncleg.gov/BillLookup/2017/S325; Restore Last Saturday Early One-Stop, Session Law 2018-129, House Bill 335. Available at https://www.ncleg.gov/BillLookup/2017/H335.

7 Analysis by Democracy North Carolina, based on data available from the State Board of Elections as of April 2019. Data retrieved from https://dl.ncsbe.gov/?prefix=ENRS/.

8 Weber, J. (2018, July 18). New state law will mean fewer places to vote early in some counties. The News & Observer. Retrieved from https://www.newsobserver.com/news/politics-government/article214589500.html

9 Paterson, B. (2018, September 24). Bipartisan Furor as North Carolina Election Law Shrinks Early Voting Locations by Almost 20 Percent. Propublica. Retrieved from https://www.propublica.org/article/bipartisan-furor-as-north-carolina-election-law-shrinks-early-voting-locations-by-almost-20-percent.

10 Olgin, A. Early Voting Changes In North Carolina Spark Bipartisan Controversy. NPR. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2018/10/17/657928248/early-voting-changes-in-north-carolina-spark-bipartisan-controversy

11 See supra note 8.

12 Paterson, B. (2018, September 24). Bipartisan Furor as North Carolina Election Law Shrinks Early Voting Locations by Almost 20 Percent. Propublica. Retrieved from https://www.propublica.org/article/bipartisan-furor-as-north-carolina-election-law-shrinks-early-voting-locations-by-almost-20-percent. Bladen County was the center of an vote tampering scheme which lead the State Board of Elections to call for a new election in Congressional District 9. The scheme involved mail-in absentee ballots and, among other things, highlights the need to ensure that every voter have the opportunity to cast an in-person ballot. In addition, the State Board of Elections investigation found that Bladen County poll workers improperly counted votes early, as a result of faulty training.

13 Id.

14 “Flexible scheduling” is defined here as opening satellite sites for only part of the Early Voting period, when demand for them is highest.

15 In many counties the main site is at the County Board of Elections, but counties can also designate an “in lieu of” site as the main site, which is typically near the County Board of Elections office.

16 Analysis of historical Early Voting plans by Democracy North Carolina and ACLU-NC. Plans on file with Democracy NC.

17 Analysis of historical early voting plans by Democracy North Carolina and ACLU-NC. Plans on file with Democracy NC. Site Reductions: Alamance, Ashe, Bertie, Bladen, Brunswick, Buncombe, Caldwell, Carteret, Caswell, Columbus, Craven, Cumberland, Dare, Davie, Gaston, Gates, Guilford, Halifax, Harnett, Henderson, Iredell, Johnston, Lincoln, Madison, Mcdowell, Mecklenburg, Nash, Northampton, Onslow, Person, Pitt, Polk, Richmond, Rowan, Rutherford, Sampson, Stanly, Surry, Transylvania, Vance, Wayne, Wilkes, Wilson. Weekend Day Reductions: Alexander, Alleghany, Ashe, Avery, Beaufort, Bertie, Caldwell, Camden, Carteret, Caswell, Chowan, Clay, Columbus, Craven, Currituck, Davidson, Davie, Edgecombe, Gates, Haywood, Hertford, Hoke, Hyde, Iredell, Jackson, Lincoln, Macon, Madison, Martin, Mcdowell, Mitchell, Nash, Northampton, Onslow, Pasquotank, Perquimans, Rowan, Scotland, Stokes, Transylvania, Tyrrell, Vance, Warren, Washington, Wilkes, Yadkin, Yancey. Weekend Hour Reductions: Alamance, Alleghancy, Ashe, Avery, Beaufort, Bertie, Brunswick, Buncombe, Caldwell, Camden, Carteret, Caswell, Chowan, Clay, Cleveland, Craven, Currituck, Davidson, Davie, Duplin, Edgecombe, Gates, Graham, Greene, Guilford, Halifax, Haywood, Henderson, Hertford, Hoke, Hyde, Iredell, Jackson, Lee, Lincoln, Macon, Madison, Martin, Mcdowell, Mitchell, Nash, Northampton, Onslow, Pasquotank, Pender, Perquimans, Person, Pitt, Polk, Richmond, Rowan, Rutherford, Scotland, Stanly, Stokes, Surry, Transylvania, Tyrrell, Vance, Warren, Washington, Wayne, Wilkes, Yadkin, Yancey.

18 Analysis of historical early voting plans by Democracy North Carolina and ACLU-NC. Plans on file with Democracy NC.

19 Gutiérrez, I. and Hall, B. (2017, June). Alarm Bells from Silenced Voters. Democracy North Carolina. Retrieved at https://democracync.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/SilencedVoters.pdf; Gutiérrez, I. (2018, July). From the Voter’s View: Lessons from the 2016 Election. Democracy North Carolina. Retrieved from https://democracync.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/PostElectionReport_DemNC_web.pdf

20 Dukes, T. (2018, November 1).Full methodology: 2018 Early voting analysis. WRAL. Retrieved from https://www.wral.com/methodology-2018-early-voting-analysis/17960039/. Supplementary data available at https://github.com/mtdukes/evl-analysis/blob/master/postgres-analysis.sql.

21 Letter from Isela Gutiérrez, Research and Policy Director, Democracy North Carolina and Emily Seawell, Staff Attorney, American Civil Liberties Union of North Carolina to Kristin Scott, Director Of Elections, Halifax County, Re: Senate Bill 325 and Early Voting in Halifax County (2018, July 2) (on file with authors).

22 Analysis of historical early voting plans by Democracy North Carolina and ACLU-NC. Plans on file with Democracy NC. Dukes, T. (2018, November 1).Full methodology: 2018 Early voting analysis. WRAL. Retrieved from https://www.wral.com/methodology-2018-early-voting-analysis/17960039/. Supplementary data available at https://github.com/mtdukes/evl-analysis/blob/master/postgres-analysis.sql.

23 See supra note 20.

24 Both Jones and Pamlico counties received federal recovery assistance following Hurricane Florence. North Carolina Office of the Governor. (2018, Sept 28). Greene Becomes 28th County Eligible for Florence Disaster Assistance. Retrieved from https://governor.nc.gov/news/greene-becomes-28th-county-eligible-florence-disaster-assistance

25 Paterson, B. (2018, September 24). Bipartisan Furor as North Carolina Election Law Shrinks Early Voting Locations by Almost 20 Percent. Propublica. Retrieved from https://www.propublica.org/article/bipartisan-furor-as-north-carolina-election-law-shrinks-early-voting-locations-by-almost-20-percent

26 Dukes, T. (2018, November 1) Early voting changes hit NC rural voters hardest, analysis shows. But will it matter in 2018? WRAL.com. https://www.wral.com/early-voting-changes-hit-nc-rural-voters-hardest-but-will-it-matter-in-2018-/17959224/

27 Urban, rural, and suburban classifications from the NC Rural Center, available here https://www.ncruralcenter.org/about-us/.

28 Hertford, Edgecombe, Bertie, Northampton, Halifax, Vance, Warren, Washington

29 The Uniform & Expanded Early Voting Act, Session Law 2018-112, Senate Bill 325. Available at https://www.ncleg.gov/BillLookup/2017/S325; Restore Last Saturday Early One-Stop, Session Law 2018-129, House Bill 335. Available at https://www.ncleg.gov/BillLookup/2017/H335.

30 Analysis of historical early voting plans by Democracy North Carolina and ACLU-NC. Plans on file with Democracy NC. Analysis by Democracy North Carolina, based on data available from the State Board of Elections as of April 2019. Data retrieved from https://dl.ncsbe.gov/?prefix=ENRS/.

31 Orange County is classified as a Suburban County by the NC Rural Center.

32 Analysis by Democracy North Carolina, based on data available from the State Board of Elections as of April 2019. Data retrieved from https://dl.ncsbe.gov/?prefix=ENRS/.

33 Since voter registration forms did not include a “Hispanic/Latino” classification until 2002, since many voters skip that question on the form, and based on comparisons with Census Bureau data, there are likely many more Latinx voters on the rolls than those reflected in State Board of Elections data. Read more from Gutiérrez, I. and Hall, B. (2012, July). A Snapshot of Latino Voters in North Carolina. Available at https://democracync.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/snapshot-of-latino-voters-in-nc.pdf.

34 Analysis by Democracy North Carolina, based on data available from the State Board of Elections as of April 2019. Data retrieved from https://dl.ncsbe.gov/?prefix=ENRS/.

35 Allow Early Voting/Last Saturday/Flexibility, House Bill 893. Available at https://www.ncleg.gov/Sessions/2019/Bills/House/PDF/H893v1.pdf.

MEDIA CONTACT: Jen Jones, 919-260-5906, jen@democracync.org

DATA QUESTIONS/REQUESTS: Sunny Frothingham, 919-908-7941, sunny@democracync.org

Democracy North Carolina is a statewide nonpartisan organization that uses research, organizing, and advocacy to increase civic participation, reduce the influence of big money in politics, and remove systemic barriers to voting and serving in elected office.