Executive Summary: NC’s 2020 Primary Reveals Challenges Facing Voters in a Pandemic

As voters and elections officials face uncertainty about our upcoming elections in light of the global public health crisis caused by COVID-19, Democracy North Carolina is working to protect all North Carolinians’ access to the ballot. This report seeks to offer a comprehensive review of lessons from North Carolina’s March 2020 primary by reviewing information in two key areas: first, voter participation patterns and trends in the North Carolina 2020 primary, including data on mail-in absentee voting, and second, the voter experience as documented through our statewide poll monitoring program and hotline. And as federal and state leaders, courts, and advocates are making decisions to anticipate and address COVID-19 election needs, the report also details solutions to address both perennial election administration challenges and new ones presented by COVID-19.

This voter participation data section is based on Democracy North Carolina staff’s review of publicly available data for 92 of North Carolina’s 100 counties available through the State Board of Elections. The voting experience finding is based on a review of narratives from voters who sought assistance during the primary from the nonpartisan hotline and poll monitoring network that we coordinate in partnership with state and national partner organizations. The report’s policy recommendations are based on these data and narratives, prior recommendations, and observations from elections in other states.

2020 Primary Election Report

Download the full report here.Key Insights from the 2020 Primary

- A large majority (65%) of North Carolina’s fastest-growing political group — unaffiliated voters — chose to cast a Democratic ballot during the primary.”1 And this trend shows no signs of slowing down. In fact, in every year since 2014, a plurality of new voters in North Carolina has registered as unaffiliated. If this trend continues, it won’t be long before unaffiliated voters surpass Democrats to become the largest group of registered voters in North Carolina.

- As stakeholders at the federal and state levels grapple with voting by mail amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the vast majority of North Carolina primary voters chose to cast in-person ballots during early voting and Election Day, signaling the need for policy changes that address safe and secure in-person options this fall.

- Regarding early voting, thanks to advocacy on the state and local levels, North Carolina counties were able to offer roughly 1,380 more weekend hours and more sites for voters in the 2020 primary than in 2016. This is due in part to the 2016 restoration of a 17-day early window as a result of litigation, and to 2019 legislation that required an extra two hours of voting on the last Saturday compared to 2016.

- Even after June 2020 legislative changes to the state’s absentee voting process, it’s worth noting that nearly one in five mail-in votes by Black voters were rejected in North Carolina’s 2020 primary, with most (40%) declined due to missing signatures.

- Following a year in which over 570,000 North Carolina voters were removed from the voting rolls, most provisional ballots cast in the state’s 2020 primary were due to lack of registration.

- As election officials anticipate a dramatic increase in absentee-by-mail voters this fall, many of the absentee-by-mail voters seeking assistance from Democracy North Carolina following the 2020 primary reported: (1) Lack of clarity on how to request an absentee ballot and who could assist them with it and (2) Lack of equipment needed to print an absentee ballot request form.

If you have questions about this report, please reach out to Alissa Ellis (Advocacy Director) at alissa@democracync.org.

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Section I: Electoral participation in the 2020 primary

- Voter Turnout

- Key Demographics in Early Voting

- Key Demographics on Election Day

- Section II: Election protection and the voter experience in the 2020 primary

- Election Protection Overview

- The Voter Experience

- Section III: Solutions to Increase Voter Access

Section I: Electoral participation in the 2020 primary

With this report, Democracy North Carolina provides data-driven analysis and recommendations for expanding voter access amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Understanding electoral participation in the 2020 primary will help to inform election administration for the upcoming general election, which may be shaped by both high turnout and the public health crisis posed by COVID-19. This section will detail findings from a review of data regarding turnout across both early voting and election day, mail-in absentee ballot usage, provisional ballot usage, and curbside voting. As our legislature and elections administrators consider how to best address necessary changes to our elections during this public health crisis, including preparation for significant expansion of voting by mail, this information provides valuable insights in the ways in which North Carolinians vote and the potential impact of substantial changes to our elections to safeguard from unintentional disenfranchisement of historically marginalized communities.

Voter Turnout in the 2020 Primary

We begin by looking at overall trends in voter turnout for the 2020 primary. The media often focuses on analyzing voter turnout in order to predict outcomes for upcoming elections. But fully understanding both turnout data itself and its implications requires accounting for changing demographics within the electorate and the complexity of tracking turnout through various election cycles (e.g. years with non-presidential races, varying early voting periods, and other factors). We hope that our analysis will contribute to the public’s understanding of voter turnout in North Carolina and help to inform initiatives focused on voter engagement for the upcoming election, including key voter education activities, get-out-the-vote efforts, and voter outreach outside of political campaigns.

Our Methodology

We calculate voter turnout rates by dividing the number of voters who cast ballots by the number who were eligible to cast ballots. For some demographic groups, (Asian voters, Latinx voters, and 17-year-olds) there was a disproportionate increase in registered voters, which led to drops in the turnout rate, even though the number of voters who cast ballots increased compared to the previous cycle. Another way to think about it is that instead of the “slice” of voters who cast ballots growing within a static population, the entire “pie” of voters got bigger. The full data for the 2020 primary, including Election Day, is not yet available from the State Board of Elections. Our picture of statewide turnout rates, then, compares the 2020 data for the 92 counties for which data is available to the corresponding data from those same counties in 2016.2

There are always complications in comparing one election to another, especially given the frequent changes in North Carolina election law over the course of the last decade. For the purposes of this report, we used the 2016 primary for comparison, but there are some important differences between that primary and the March 2020 primary. The 2016 primary was the most recent Presidential and Senatorial primary, but it operated under different election rules: the early voting period was 10 days instead of 17 days in 2016 and voters were asked to show identification to vote. Additionally, the 2016 primary had competitive Presidential primaries for both major political parties.

Turnout in the 2020 primary3

From the data available, it appears that turnout in the 2020 primary was down overall compared to the corresponding 2016 primary, which was anticipated since only one of the major parties had competitive presidential and senate primaries. Accordingly, turnout among registered Republicans dipped: 221,500 fewer Republicans voted, for a 13 percentage point drop in the turnout rate, from 43% in March 2016 to 29% in March 2020, in the 92 counties for which full data are available. A corresponding drop occurred in the number of white voters, who cast 226,700 fewer ballots in March 2020, a 6 percentage point drop in the turnout rate compared to March 2016.

Party turnout in the 2020 primary

In contrast to the drop in Republican voter turnout, almost 18,000 additional Democratic voters cast ballots in the 2020 primary in the 92 counties for which full data are available, for a two percentage point increase in the turnout rate, from 35% in March 2016 to 37% in March 2020. An additional 39,600 voters registered as unaffiliated cast ballots in the 2020 primary— but since the number of registered unaffiliated voters has grown by over 400,000 voters in that time period, the unaffiliated turnout rate decreased by a few percentage points. In the 2020 primary, 65% of the registered unaffiliated voters who voted cast Democratic Party Ballots, while 34% cast Republican Party Ballots. Libertarian turnout dipped slightly, while the Constitution Party and the Green Party, both of which gained state recognition after the last presidential election, garnered around 300 votes each in the 92 counties for which full data are available.

Voters who reject party labels overwhelmingly chose to vote for Democrats in North Carolina’s 2020 primary. As noted above, a large majority (65%) of North Carolina’s fastest-growing political group4 — unaffiliated voters — chose to cast a Democratic ballot during the primary; this fact was shaped at least in part by a contested and high-profile Democratic presidential primary.

This information is especially noteworthy because of the substantial increase in the unaffiliated voter population both as a whole and as a share of the state’s registered voters— in every year since 2014, the plurality of new voters in North Carolina are registering as unaffiliated. If this continues, it will not be long before unaffiliated voters surpass Democratic voters to become the largest group of registered voters in North Carolina.

Black voter turnout in the 2020 primary

The turnout rate for Black voters remained constant from the 2016 to the 2020 primary. An additional 16,900 Black voters cast ballots in the March 2020 primary, bringing the number of Black voters to 410,000 compared to 393,100 during the March 2016 primary in the 92 counties for which full data are available. An increase of 35,300 registered voters accompanied the increase of Black voters who cast a ballot, resulting in a turnout rate of 30 percent, identical to the 2016 primary.

Asian American voter turnout in the 2020 primary

The turnout rate for Asian American voters was slightly lower in the March 2020 primary (20%) than in the March 2016 primary (21%) in the 92 counties for which full data are available, but those rates alone are misleading. An additional 4,400 voters cast ballots, bringing the number of Asian American voters to 17,300 compared to 12,900 during the March 2016 primary. The turnout rate dipped because an additional 26,600 Asian American voters registered this cycle— the number of Asian American registered voters increased 43% from March 2016 to March 2020.

Native American voter turnout in the 2020 primary

Voter registration numbers stayed constant for Native American voters. However, the turnout rate fell slightly in the 2020 primary (23%) compared to the 2016 primary (27 percent). 1,600 voters cast ballots, bringing the number of Native American voters down to 12,275 compared to 13,903 during the March 2016 primary in the 92 counties for which full data are available.

Latinx voter turnout in the 2020 primary

Similar to the pattern we saw for Asian American voters, about 6,400 more Latinx voters cast ballots in the 2020 primary, up from 26,000 in the 2016 primary to 33,000 in the 2020 primary, but the turnout rate actually decreased from 21% to 17% because of a marked increase in Latinx voters who are registered to vote. Since the 2016 primary, 71,200 Latinx voters have registered to vote— a 57% increase in the number of registered Latinx voters compared to March 2016 in the 92 counties for which full data are available.

Youth voter turnout in the 2020 primary

Voters within the age range of 18 to 25 cast slightly fewer ballots this cycle than in the 2016 primary, casting 123,600 ballots in 2020 compared to 143,000 in 2016 in the 92 counties for which full data are available. Seventeen-year-olds who will be 18 by the time of the 2020 General Election in November were eligible to vote in the March 2020 primary. Since the March 2016 primary, the ability for 16 and 17 year olds to preregister to vote has been restored, which meant 35,600 more 17 year olds (from 12,800 in 2016 to 48,400 in 2020) were registered to vote in the March 2020 primary than in the March 2016 primary. The number of 17 year olds who cast ballots grew by a third (2,300) compared to 2016.5

Voting Method in the 2020 primary

As state and federal leaders debate whether to expand voting by mail amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the vast majority of North Carolina primary voters chose to cast in-person ballots during early voting and Election Day, signaling the need for policy changes that address safe and secure in-person options this fall.

Voters use a variety of methods to cast their ballots: the most popular methods in North Carolina are casting ballots in-person on Election Day or in-person during early voting, followed by voting by mail with an absentee ballot. Voters who need to use curbside voting to access the polling site can do so throughout the cycle at early voting sites and at Election Day polling places. Some voters who present to vote during early voting or on Election Day will need to cast provisional ballots. Again, because the State Board of Elections’ publicly available files are incomplete, we do not have the full picture. From the 92 counties with full available data, 62% of voters cast their ballots in-person on Election Day, and 35% cast their ballots in-person at early voting sites. A small percentage of voters cast their ballots using curbside voting and mail-in absentee voting.6 As the state and federal leaders debate whether to expand voting by mail amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the vast majority of North Carolina primary voters chose to cast in-person ballots during early voting and Election Day, signaling the need for policy changes that address safe and secure in-person options this fall.

Broadly, it is not surprising that a larger proportion of voters may wait until Election Day to vote in primaries than in general elections in North Carolina. In a primary, voters’ top choices may shift, or they may want to wait until the last possible moment to make sure their preferred candidate is still in the race. We usually anticipate that a much larger proportion of voters will vote before Election Day in a general election, since more voters are attentive to contests and may also have their top choices locked in, at least for the races at the top of the ballot. In the 2016 General Election, for example, 62% of voters cast their ballots during early voting (including curbside), 33% cast ballots in person on Election Day (including curbside), and only 4% of voters used mail-in absentee voting.

Looking ahead to the 2020 General Election, an examination of which voters use which methods of voting aids in understanding administrative barriers to voting access. Especially in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s important to understand the barriers to access that exist in different voting methods, since certain methods may involve more transmission risk than others. Recommendations are set forth in Section III that address the barriers to access raised in this report.

Key Demographics in Early Voting

Following litigation and advocacy concerning changes to early voting availability, voters had more hours and sites during the 2020 primary’s early voting period compared to 2016. HB 589, the restrictive 2013 elections omnibus, had a significant impact in the 2016 primary: the early voting period was truncated to only 10 days, instead of 17, voter ID was implemented, and pre-registration for 16 and 17 year olds was eliminated. While that law was struck down in 2016, 2018 legislation eliminated the final Saturday of early voting and passed a law that led many counties to eliminate early voting sites and weekend voting options.7 Ahead of the 2020 primary, legislation restored the last Saturday of early voting in all counties. Because of these outcomes, along with advocacy on the state and local levels, North Carolina counties were able to offer roughly 1,380 more weekend hours and more sites for voters in the 2020 Primary, than in 2016. The successful fight for expanded early voting options enabled the increases we see below.

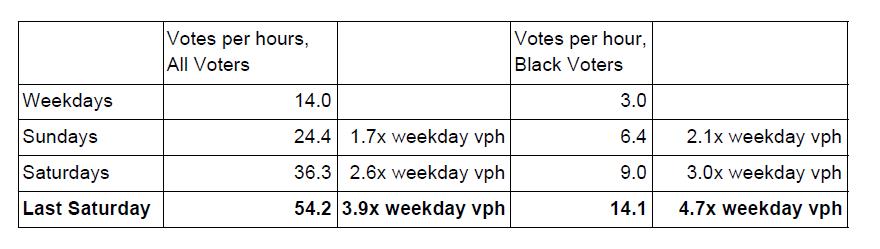

Votes Per Hour

The importance of weekend voting options is especially apparent in vote-per-hour rates. The vote-per-hour rates below are calculated by dividing the number of voters who cast in-person absentee ballots at early voting sites on a certain day by the number of hours that voting sites were open on that day. As seen below, two and a half times as many votes were cast, per hour of voting, on Saturdays compared to Weekdays in the 2020 primary. On the Last Saturday of early voting, almost four times as many votes were cast per hour than on Weekdays statewide. Even as lawmakers required counties to waste precious resources for uniform weekday hours, voters continued to prove the overwhelming importance and usage of weekend voting.

The trend is especially notable for Black voters, who cast three times as many votes per hour on Saturdays, more than twice as many votes per hour on Sundays, and more than four and a half times as many votes per hour on the last Saturday of early voting than on weekdays.8

Two and a half times as many votes were cast, per hour of voting, on Saturdays compared to Weekdays in the 2020 primary. The trend is especially notable for Black voters, who cast three times as many votes per hour on Saturdays, more than twice as many votes per hour on Sundays, and more than four and a half times as many votes per hour on the last Saturday of early voting than on weekdays.

Overall, more voters utilized early voting in 2020 than in 2016

In the 2020 primary, more than 779,000 voters cast ballots at early voting sites, compared to about 686,000 in 2016. Black voters cast 12% more ballots at early voting sites and white voters cast 10% more ballots at early voting sites. Notably, Asian voters cast 64% more ballots at early voting sites this cycle compared to 2016. In addition, Latinx voters cast 41% more ballots at early voting sites, multiracial voters cast 20% more ballots at early voting sites, and native voters cast 3% fewer ballots at early voting sites in 2020 compared to 2016. 15,600 voters, 2% of the voters who cast ballots at early voting sites in the 2020 primary, used Same-Day Registration during the early voting period in 2020, to register to vote or to update their registration.

Partisan Breakdown

Along party lines, a third more Democratic ballots were cast at early voting sites this year than in 2016: 508,700 ballots were cast in 2020 compared to 384,300 ballots in 2016.9 Fewer Republican ballots were cast at early voting sites this cycle than in 2016, which is not surprising given that there was not a competitive presidential primary on the Republican ballot this cycle, and there was a dip in Republican voter turnout across voting methods. Libertarian ballots cast at early voting sites increased by 16 percent: 1,500 ballots were cast in 2020, compared to 1,300 ballots cast in 2016. Additionally, 64 voters cast Constitution party ballots and 114 voters cast Green party ballots at early voting sites in the March 2020 primary.

Key Demographics on Election Day

Mail-In Absentee Voting

As voters face the difficult decision of how to vote in the upcoming elections, it is important to understand how mail-in absentee voting has been utilized historically in North Carolina. North Carolina has no excuse mail-in absentee voting, which means that “no special circumstance or reason is needed to receive and vote a mail-in absentee ballot.”10 Mail-in absentee ballot request forms were not mailed to all eligible voters in the 2020 primary, which is a significant barrier for many voters.

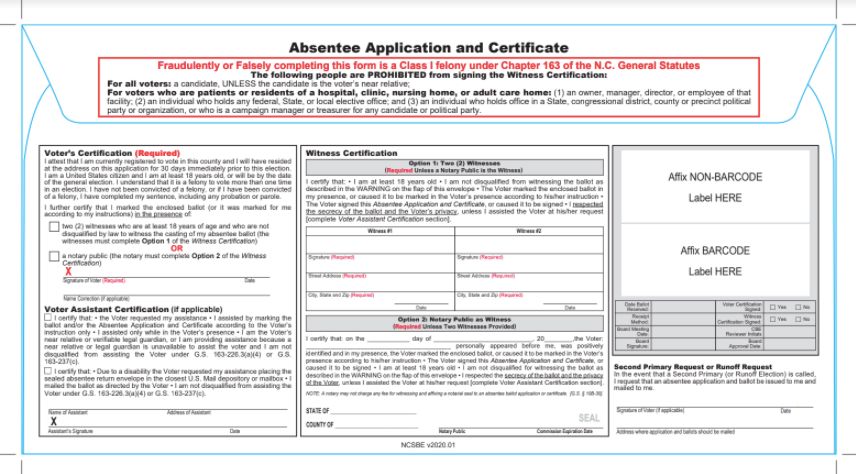

Even with changes put in place by June 2020 legislation,11 the process for voting by mail with an absentee ballot is complex in North Carolina:12

- First, a registered voter, near relative, or legal guardian, must submit an absentee ballot request form. The legislation passed in June 2020 allows voters to submit this form online and directs the State Board of Elections to establish a website for public use.

- Until that online option is ready, the completed and signed request form must be returned in-person by the voter, legal guardian, or close relative to an authorized delivery service (U.S. Postal Service, USPS, FedEx, or DHL), or multipartisan assistance team to the voter’s county board of elections.

- When the request form is received and approved by the voter’s county board of elections, a ballot is mailed to the voter.

- A voter who receives their ballot for the 2020 general election must complete that ballot in the presence of a single witness. This is a 2020-only modification of standard rule requiring a voter to complete their ballot in the presence of two witnesses or one notary. When the ballot is completed, the voter and the witness must sign the appropriate certification space on the return envelope and return the ballot to the county board of elections by 5:00 PM on Election Day.

Ten days after Election Day, counties hold a canvass meeting to verify that votes are counted and tabulated properly. Mail-in absentee ballots go through a process of signature verification. Election officials compare and match the voter signature to other voter documents they have on file to confirm that the ballot is lawful.

Ballots can be rejected for a variety of reasons, like arriving late or lacking the proper signatures. If a voter makes a mistake on their ballot (for example, by not signing it or failing to get the required witnesses to sign it) and returns their ballot in time for their county to send them a new one, the first one is marked as “spoiled” and voided so that the county can provide them with a new one. If the county does not have time to send voters who made a mistake on their ballot a new absentee-by-mail ballot, then the voter’s only options are to cast a ballot in person during the final days of early voting or on Election Day.

At least some counties attempt to notify voters if their absentee-by-mail ballot will not count, but these efforts can be hampered by lack of contact information and lack of election staff capacity in the days leading up to the election. If an unprecedented number of North Carolinians need to utilize absentee-mail-in voting this fall due to COVID-19, county boards of elections will need significant increases in staff capacity to be able to process ballots and send out new ones, as needed, in a timely manner.

When a ballot is marked as “spoiled,” that means that the voter who requested the ballot was sent a new one or that the voter cast their ballot in person. Data suggests that some voters attempted to cast absentee ballots up to four times due to various mistakes in filling out the ballot or the accompanying witness and signature requirements in 2016.13 Because some voters try multiple times to cast an absentee ballot, the totals below reflect the number of ballots rejected instead of the number of voters who requested them.

Mail-in absentee ballot requests in the 2020 election compared to 201614

Amid new restrictions, North Carolinians cast fewer votes by mail in the 2020 primary than in 2016: voters requested 41,400 mail-in absentee ballots in the 2020 primary. This is 11,000 fewer than requested in 2016.

- Requests from Black, white, and Native American voters declined by 40%, 24%, and 70%, respectively. In contrast, requests from Asian voters increased 50% and requests from Latinx voters increased 19%, compared to 2016.

- There was a significant drop in Republican mail-in absentee ballot requests compared to 2016. Without a competitive Presidential race to incentivize registered Republicans to vote, voters requested 9,821 fewer ballots compared to 2016. Of all ballots requested by Republicans, 75% were returned and 87% were accepted.

- Democratic mail-in absentee ballots requested decreased by 5 percent: 19,478 ballots were requested in 2016 compared to 18,381 ballots requested in 2020. 77% of Democratic ballots were returned, and 86% of all returned ballots were accepted.

- Finally, a majority of all Constitution and Libertarian ballots were accepted and half of all returned Green ballots were accepted.

Rejection rates15

Elections officials are expecting a surge in mail-in voting amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Traditionally, mail-in absentee ballots account for 4% to 5% of all votes, but the North Carolina State Board of Elections projects mail-in absentee ballots could make up 30% to 40% of votes this fall.16 The rejection rates detailed below highlight the complexities of mail-in absentee voting. If rejection rates this fall mirror rates from the 2020 primary and more voters elect to vote from home, we could see a large number of rejected mail-in absentee ballots.

Statewide and across most demographics, voters returned fewer ballots during the 2020 primary (75%) compared to 2016 (79%). Of the ballots returned, 86% were accepted and 14% were rejected (a one percentage point increase in rejections from 2016).17 It’s worth noting that, as discussed below, 39% of the rejected ballots led to new ballots being sent— so this figure reflects a total number of rejected ballots as opposed to the total number of voters affected. That said, that rate also reflects the challenges voters generally face in the absentee process.

1 in 7 mail-in absentee ballots returned in the 2020 primary was rejected.

1 in 7 mail-in absentee ballots returned in the 2020 primary was rejected.

Mail-in absentee rejection rates are lowest for white and Native American voters in North Carolina, but higher for Black voters (18%), Asian voters (15%), Multiracial voters (15%), and Latinx voters (15%). Thirty-nine counties had rejection rates higher than the state average.18 Nineteen counties had a rejection rate of 20% or higher.19

Top reasons for rejection statewide:

- 39% of the ballots that did not count were “spoiled,” meaning that the county sent the voter a new ballot;

- 35% percent of the ballots that did not count had missing voter signatures;

- 18% were returned after the deadline; and

- 6% had incomplete witness information.

Black voter mail-in absentee ballot usage in the 2020 Primary

Nearly one in five mail-in votes by Black voters were rejected in North Carolina’s 2020 primary, with most (40%) declined due to missing signatures. Eighteen percent of the ballots returned by Black voters were rejected: the highest rejection rate among any racial or ethnic group and a four percentage point increase from 2016. Thirty-one percent of the ballots returned by Black voters that did not count were spoiled and reissued. Forty percent of the rejected ballots were missing a voter’s signature, 15% were returned after the deadline, and 12% of the absentee mail-in ballots returned by Black voters were rejected because of missing witness information.

Asian voter mail-in absentee usage in the 2020 Primary

Of all mail-in absentee ballots requested by Asian American voters, 72% were returned. Of those returned ballots, 85% were accepted. Fifteen percent of the ballots returned by Asian voters were rejected, slightly higher than the statewide average and a two percentage point increase from 2016. Thirty-one percent of the ballots returned by Asian voters that did not count were spoiled and reissued. Thirty-five percent of the ballots rejected were returned after the deadline, and 29% were missing voter signature. Additionally, 3% of the absentee mail-in ballots cast by Asian voters were rejected because of a signature mismatch and 3% had incomplete witness information.

Latinx voter mail-in absentee ballot usage in the 2020 Primary

Of all mail-in absentee ballots requested by Latinx voters, 72% were returned. Of the returned ballots, 85% were accepted. Fifteen percent of the ballots returned by Latinx voters were rejected. Notably, the rejection average decreased by five percentage points compared to 2016 but is still slightly higher than the statewide average. Forty-two percent of the ballots returned by Latinx voters that did not count were spoiled and reissued. This rate of spoilage was especially high, potentially pointing to a need for increased availability of voter education materials, ballots, and ballot instructions in Spanish. Twenty-five percent were returned after the deadline and 7% of the absentee mail-in ballots cast by Latinx voters were rejected because of missing witness information.

Age and voter mail-in absentee ballot usage in the 2020 Primary

Mail-in absentee voting was disproportionately utilized in the 2020 primary by both youth and elders: voters 18 to 25 years old made up 6% of voters in the 2020 primary, but 17% of those who used absentee by mail voting. Voters over the age of 66 made up 32% of voters in the 2020 primary, but 46% of those who cast absentee mail-in ballots. Notably, both youth and elders who voted by mail had higher rejection rates than the statewide average.

- Seventeen percent of the ballots cast by voters 18 to 25 years old were rejected – 20% were spoiled and reissued, 45% were returned after the deadline and 32% were missing the voter’s signature.

- Under new absentee rules that limit assistance, fifteen percent of the ballots cast by voters over 66 were rejected: four percentage points higher than in 2016. Forty-three percent were spoiled and reissued, 39% were missing the voter’s signature, 10% were returned after the deadline, and 7% were missing witness information. The increase in the rejection rates for elders compared to 2016, and the especially high spoilage rate for elders may be due to recent changes in the absentee ballot process that make it harder for voters who need assistance in filling out their ballot to get that assistance. As we look ahead to the 2020 General, elders in care facilities will likely face even greater barriers in accessing assistance if care facilities continue to be severely impacted by COVID-19.

County Breakdown

Caswell, Wilson, Hyde, and Vance counties had the highest rejection rates across the state. In Caswell County, 33% of returned ballots were rejected. Most rejected ballots were missing voter signatures. In Wilson county, 34% of ballots were rejected. In most cases, ballots were returned after the deadline. In Hyde County, voters requested eighteen mail-in absentee ballots and returned fourteen. 36% of all returned ballots were rejected. In Vance County, 44% of returned ballots were rejected. 84% of all rejected ballots were spoiled ballots.

In counties home to tribal reservations, mail-in absentee ballot requests were particularly low among Native American voters. In Robeson County, 9,031 Native American voters cast a ballot during the 2020 primary. Of those 9,031 ballots, only eleven were mail-in absentee ballots. In Cumberland county, 532 Native American voters cast a ballot during the 2020 primary and requested four mail-in absentee ballots. Similarly, out of the 422 ballots cast in Swain County, four were mail-in. These numbers are important in the context of COVID-19 and the importance of the accessibility of absentee by mail voting.

Provisional Ballots

Most voters vote in person with a standard ballot. However, a provisional ballot is offered to voters when there is a question about a voter’s eligibility to vote in a given election, at a specific precinct, or to vote a certain ballot style.

Provisional ballot usage in the 2020 election compared to 2016

About 18,300 voters cast provisional ballots in the 2020 primary Election, a major decrease from the 40,200 cast in 2016. Some of this difference might be explained by the shorter early voting period (without as many opportunities to use Same-Day Registration during early voting, more voters may have to deal with issues with their registration on election day); a portion of the difference can also be attributed to the photo voter ID requirement in place during the 2016 primary. The 2016 primary also included competitive primaries for both major political parties, which may have garnered more turnout from less frequent voters across the political spectrum, whose registration records were not up to date.

The publicly available data for 2020 remains incomplete,20 but at least 6,400 ballots were fully counted, and 1,500 were partially counted, roughly 43% of those cast. Voters who cast ballots at a different polling place than their election day precinct may have to vote provisionally – and many of these ballots “partially count” if the voter is in some different districts – their votes in the races they are eligible to vote in will be counted, but their votes in races they are not eligible to vote in will not be counted. Around 9,400 provisional ballots were rejected (51 percent), while about a thousand ballots are still listed as “pending.” The vast majority of the ballots listed as “pending” in the publicly available data are from Durham County, which was impacted by a malware attack right after the election, and was delayed in reporting their results to the State Board.

Following a year in which over 570,000 North Carolina voters were removed from the voting rolls, most provisional ballots cast in the state’s 2020 primary were due to lack of registration. The biggest reason voters cast a provisional ballot in the 2020 primary was that election officials could not find their record of registration— of over 6,000 ballots cast for this reason, only 18% were approved or partially approved, while 77% were rejected. An additional 4,600 voters cast provisional ballots because they wanted to vote in a primary other than the one currently listed in their voter registration record— 21% of these were approved or partially approved, while 75% were rejected. Over a thousand voters cast provisional ballots because their voter registration had been previously removed from the rolls by their county; this can happen for a number of reasons, including when county officials believe a voter is no longer eligible to vote or a voter does not vote consistently. This can sometimes happen erroneously; while voter list maintenance practices can help keep the voter rolls up to date, excessively broad purges can end up hindering access for eligible voters.

The vast majority of voters who cast a provisional ballot because they were at the incorrect precinct, or because they had moved to another address in the same county had their ballots count— 87% and 93% respectively.

Demographics and usage

Racial data about the voters who cast provisional ballots in the 2020 primary is incomplete – but among the provisional ballots that included racial data, Asian voters, Black voters, Native voters, and Multiracial voters were overrepresented in provisional ballots – compared to the proportion of votes cast by each group including all voting methods. For example, Black voters made up 21% of the voters who cast ballots in the 2020 primary, but 25%-26% of the voters who cast provisional ballots. The same was true for Latinx voters when looking at ethnicity data. Latinx voters made up around 2% of statewide ballots, but 4%-5% of provisional ballots that included ethnicity data.21

Voters under 40 disproportionately used provisional ballots this year: 18- to 25-year-olds made up 6% of voters in the 2020 primary, but 19% of those who voted provisionally. To put it another way, 18 to 25 year olds made up a small fraction of all voters in the primary but accounted for almost 1 in 5 provisional voters. Additionally, 26- to 40-year-olds made up 15% of voters, but 27% of those who voted provisionally.

More than half of the provisional ballots cast in the March 2020 primary were cast by Democratic voters (51%), followed by Republican voters (25%), and unaffiliated voters (22%).

Curbside Voting

Curbside voting is an essential mechanism that permits voters to vote in person from their vehicle if they are unable to enter a polling location to vote without physical assistance. This method of voting is an important accommodation for those with physical limitations.

Curbside voting in the 2020 election: In the 2020 primary, about 28,000 voters used curbside voting—15,700 during the early voting period, and 12,200 on Election Day.

Demographics and usage

Curbside voting is especially important for older voters, most notably older Black voters. Voters over 66 made up 32% of those who cast ballots in the 2020 primary, but 74% of those who used curbside voting. Black voters made up 21% of those who cast ballots in the 2020 primary, but 47% of the voters who used curbside voting. Black voters over the age of 66 made up just 6% of voters in the 2020 election, but a third of all of the voters who cast ballots using curbside voting.

Section II: Election Protection and the Voter Experience

Democracy North Carolina coordinated a large-scale nonpartisan voter assistance and election monitoring program during the 2020 primary. As in previous years, the program — branded as Election Protection — was run in coalition with partners including the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, Self Help, and the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. The Election Protection program goals for the 2020 primary election were: (1) Educate voters about their voting rights and election processes; (2) Assist voters who encounter issues at the polls, working with election officials to address problems in real time; and (3) Document voters’ experiences, using this to inform future voter advocacy and litigation.

Election Protection Overview

The Election Protection program includes two main components: a nonpartisan, statewide voter hotline, and a statewide poll monitoring program.

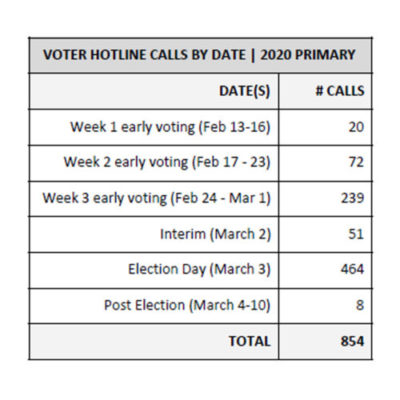

Nonpartisan Voter Hotline: Between February 13 and March 10, 2020, trained legal volunteers answered phone calls made to Democracy NC’s voter hotline (888-OUR-VOTE) and NC-specific calls made to the Lawyers’ Committee’s national Election Protection hotline (866-OUR-VOTE). Volunteers answered a total of 854 calls during this period of time.

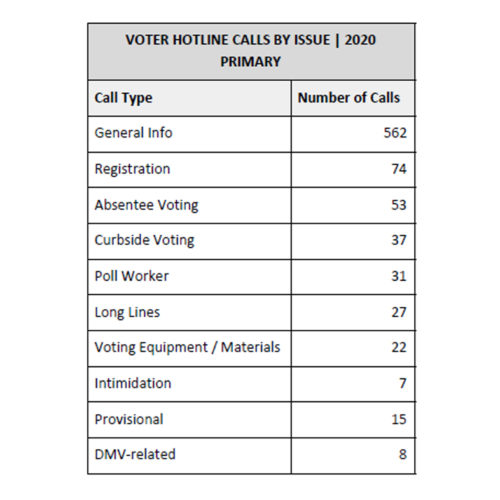

Hotline calls included requests for general information (such as polling place location and hours of operation) as well as reports of incidents that had taken place at polling places around the state. A team of voting rights experts works to address more serious issues, which are typically resolved by contacting the county board of elections.

See The Voting Experience (below) for an analysis of the hotline calls received during the 2020 primary Election.

Voter Hotline Calls by County of Caller, February 13 – March 10, 2020

Voter Hotline Calls by Date

Between February 13 and March 10, 2020, trained legal volunteers answered phone calls made to Democracy NC’s voter hotline (888-OUR-VOTE) and NC-specific calls made to the Lawyers’ Committee’s national Election Protection hotline (866-OUR-VOTE). Volunteers answered a total of 854 calls during this period of time.

Voter Hotline Calls by Issue

Hotline calls included requests for general information (such as polling place location and hours of operation) as well as reports of incidents that had taken place at polling places around the state.

Poll Monitoring Program: Democracy NC recruited and trained over 400 volunteers to monitor polling places on Election Day (March 3) and the last Saturday of early voting (February 29). A total of 168 incident reports were filed on these two days. See The Voting Experience (below) for an analysis of the incident reports received. Poll monitors were trained to assess a polling place for compliance with election law, help voters in need of assistance, and escalate issues to the nonpartisan voter hotline. See Appendix C for our methodology for precinct selection.

Early Voting Sites Monitored: On the last Saturday of early voting (February 29), 241 Vote Protectors monitored 99 one-stop voting sites in 36 counties. Poll monitors reported 34 incidents on this day.

Election Day Polling Places Monitored: On primary Election Day (March 3), 435 Vote Protectors monitored 131 polling places in 35 counties. Poll monitors reported 133 incidents on this day.

The Voting Experience

As voters face uncertainty of voting during a pandemic, it is important that stakeholders respond to existing barriers that voters face and shortcomings in the voter experience. In discussing these barriers, we also acknowledge that election administrators and poll workers have a critical and challenging role in making democracy work— their job is often unnoticed and underappreciated, especially when things work the way they should. Indeed, North Carolina’s 2020 primary avoided the systemic failures observed in other states this year, both prior and during the public health crisis. But when voters’ experiences are derailed, there are important lessons to learn and apply. That is all the more important amid the genuine pressures that officials will face conducting an election in a context shaped by changing rules, COVID-19, and the wider political environment.

The following section outlines the top issues that voters faced during North Carolina’s 2020 primary election. They inform our recommendations for common-sense changes to help all North Carolinians vote in the 2020 General Election.

Data Collection

This analysis is based on 854 phone calls from North Carolina voters and poll monitors made to the 888-OUR-VOTE nonpartisan Election Protection hotline between Thursday, February 13, and Tuesday, March 10, 2020. Our analysis also includes the first-hand accounts of over 450 poll monitors stationed at early voting sites and Election Day polling places in 35 counties around the state on Saturday, February 29, and Tuesday, March 3.

Poll monitors completed 323 polling place checklists, which assess the voting sites for appropriate signage, parking, curbside voting, and other requirements. Volunteers completed 168 incident reports, which document issues with a voting site or voter questions. Incident reports that were also reported to the 888-OUR-VOTE hotline have been removed from this data set.

While our program did not cover the majority of precincts or the experiences of all voters, it is a significant dataset providing first-person insight from the perspective of voters and poll monitors throughout the state.

This section will cover key issues that we identified in the 2020 primary, including: (1) Voter confusion about registration status, (2) Challenges with Polling Place Accessibility and Efficiency, (3) Issues with Mail-In Absentee Ballots, (4) Problems with Curbside Voting, (5) Poor Poll Worker Conduct, (6) Voting Equipment and Supply Issues, (7) Challenges with Provisional Voting, and (8) Voter Intimidation.

Voter Confusion about Registration Status & List Maintenance

As many civic engagement groups work to ensure that all eligible North Carolinians are registered to vote, it is important to understand that voter registration status is a source of confusion for many voters. Registered voters in North Carolina fall into one of two categories: active and inactive. A voter is moved from “active” to “inactive” for one of two reasons:

- Mail to the voter from the county board of elections is returned as undeliverable and the voter does not respond to an address confirmation mailing; or

- The voter fails to vote in two consecutive federal elections and the voter does not respond to an address confirmation mailing.22

Inactive voters are still registered voters and are entitled to vote in elections in which they are eligible. However, there is lingering confusion among inactive voters regarding their eligibility to vote. Complicating this matter, information on this topic does not currently exist on the NC State Board of Elections website.

Inactive voters who do not confirm or update their registration status and do not vote in two consecutive federal elections are removed from the voter rolls. This list maintenance is performed across the state every two years. Voters who are removed from the voter rolls and present to vote on Election Day do not have the option of registering to vote — their only option is to cast a provisional ballot.

In January 2019, the state of North Carolina removed 576,534 voters as part of biennial list maintenance.

During the 2020 primary Election, Democracy North Carolina received 84 reports concerning registration status from voters in the following counties: Alamance, Brunswick, Buncombe, Catawba, Chatham, Cumberland, Davidson, Durham, Edgecombe, Forsyth, Granville, Guilford, Halifax, Harnett, Henderson, Iredell, Johnston, Mecklenburg, Nash, Onslow, Pender, Randolph, Stanly, Union, Vance, Wake.

The 888-OUR-VOTE hotline received nearly 30 calls from voters marked as “inactive.” These voters expressed confusion regarding their ability to cast a ballot on Election Day. Callers sought information on how they could be moved into the “active” status, including what identification they needed to make this change.

A smaller group of voters (under 10) reported being removed from the voter rolls. These voters largely were confused about why they had been removed and inquired about the process for re-registering. An even smaller number of voters reported registering to vote, but were listed as “denied.”

Challenges with Polling Place Accessibility and Efficiency

Voting sites should be easy for voters to locate and navigate. Unfortunately, voters sometimes encounter barriers that make the process of casting a ballot challenging. These include being unable to find the correct location where voting is taking place, being unable to park their car or navigate the parking lot, or spending more than 30 minutes in line waiting to vote.

During the 2020 primary election, Democracy North Carolina received 63 reports concerning polling place accessibility and efficiency from voters in the following counties: Alamance, Buncombe, Chatham, Cumberland, Durham, Forsyth, Granville, Guilford, Halifax, Lee, Mecklenburg, New Hanover, Orange, and Wake.

Our data shows 30 unique reports of long lines at voting sites on the last day of early voting (Saturday, February 29, 2020) and Election Day (Tuesday, March 3, 2020). Voters called to report long lines (30 minutes or more) to reach the front desk, with several voters reporting waiting more than one hour. These calls came from voters in Buncombe, Chatham, Cumberland, Durham, Forsyth, Guilford, Lee, Mecklenburg, Orange, and Wake counties.

Other reports highlighted a lack of signage designating the location as a polling place or a lack of signage directing voters from the parking lot to the specific room where voting was taking place. At least one voter reported that their polling place failed to open on time.

Several voters with mobility issues reported having to walk long distances (one mile or more) from the nearest available parking to the voting area. Voters also reported parking lots that were full, congested or impossible to navigate — especially at polling places contained inside schools and recreation centers. Lastly, a small number of voters with mobility needs reported a lack of elevators and ramps for polling places with stairs.

Issues with Mail-In Absentee Ballots

In 2019, North Carolina changed its rules for how voters may request a mail-in absentee ballot. The new rules mandate that the request form must be completed by “a registered voter or [the] voter’s near relative or verifiable legal guardian.” The instructions for completing the absentee ballot request take up an entire page in 10-point font.23

Many of the absentee-by-mail voters seeking assistance from Democracy North Carolina during the 2020 primary reported: (1) lack of clarity on how to request a ballot and who could assist them with it, (2) lack of equipment needed to print a request, and (3) failure to receive a ballot, forcing them to vote in-person or miss the election altogether.

During the 2020 primary Election, Democracy North Carolina received 52 reports concerning absentee ballots in the following counties: Ashe, Avery, Bertie, Buncombe, Carteret, Chatham, Cumberland, Dare, Durham, Forsyth, Guilford, Iredell, Lincoln, Mecklenburg, New Hanover, Orange, Pitt, Randolph, Robeson, Union, Vance, Wake, and Wayne.

An analysis of voter reports shows a lack of clarity regarding how a voter can request a mail-in absentee ballot and who can assist the voter in this process. Several voters said they needed assistance, but did not have a nearby relative to assist them. These voters were instructed to call their county board of elections for help.

Voters also reported lacking the necessary equipment needed to print an absentee ballot request form off of the State Board of Elections’ website. This includes voters of all ages, who lacked a computer, internet, and/or a printer. Additionally, several voters stated that they requested, but did not receive, an absentee ballot. Others reported that their absentee ballot was mailed to the wrong address, forcing them to either vote in person or miss the election.

Problems with Curbside Voting

Every polling place in the state of North Carolina is required to offer curbside voting to those with physical disabilities. Voters who have trouble walking to the polling place or standing in line can instead vote from the comfort of their vehicle.

Each polling place should have a designated, clearly marked location for curbside voters, a method for those voters to let polling place officials know that they are outside waiting, and a poll worker whose job it is to attend to curbside voters. Even though it has been in place for decades, curbside voting is not well known or understood by most voters. And reports show that too many of those who do know about the option cannot locate the curbside voting location, or may spend an hour or more waiting to vote via curbside.

Democracy North Carolina’s voter hotline documented many issues with curbside voting for those unable to make it inside polling places during the 2020 primary across more than a dozen North Carolina counties. Additionally, we anticipate that there will be an increase in the number of curbside voters due to COVID-19 this fall.

During the 2020 primary Election, Democracy North Carolina received 43 reports concerning curbside voting in the following counties: Bertie, Buncombe, Cumberland, Durham, Forsyth, Guilford, Halifax, Haywood, Lenoir, Mecklenburg, Northampton, Orange, Rowan, and Wake.

The majority of voters and poll monitors reported that curbside voting at their site was either inefficient or confusing. Some reported that poll workers were unresponsive to curbside voters, leading to voters driving away and/or long lines (30 minutes or more). At least one report documented a site that forced voters to exit their vehicles in order to reach the buzzer to call a poll worker to their car. Another site simply listed a phone number asking voters to call if they needed to use curbside voting, leaving voters without phones unable to alert a poll worker to their presence. Given the high likelihood that curbside voting will increase significantly, these challenges must be addressed well in advance of the 2020 General Election.

Poor Poll Worker Conduct

Poll workers play a critical and underappreciated role in our elections. They are tasked with checking in voters, providing ballots, answering questions, troubleshooting problems, and providing a positive voting experience. Poll workers include three Election Judges (who are appointed by their political party and receive training) as well as election assistants and help desk workers.

In addition to being the on-the-ground representatives of North Carolina’s elections system, poll workers are also often its gatekeepers; they have significant influence over who gets to vote and who is turned away. When poll workers misunderstand or misapply election rules, they run the risk of disenfranchising eligible voters. Many voters express gratitude for poll workers’ service upon leaving their polling place. However, when voters have negative experiences with poll workers, it can lead them to question the fairness and efficacy of the entire elections system.

Voters in dozens of NC counties who sought assistance from Democracy North Carolina during the 2020 primary reported concerns with poll worker conduct, including workers who provided inaccurate information and/or made partisan comments inside the polling enclosure.

During the 2020 primary election, Democracy North Carolina received 41 reports concerning poll workers in the following counties: Bertie, Brunswick, Buncombe, Crave, Cumberland, Durham, Forsyth, Guilford, Halifax, Iredell, Johnston, Mecklenburg, Nash, New Hanover, Northampton, Orange, Rutherford, Vance, and Wake.

A small handful of voters reported poll workers who made inappropriate or partisan comments during the voting process (see narrative section for detailed accounts). Other voters reported receiving factually inaccurate information about voting rules from poll workers. In Buncombe County, a voter reported being denied a ballot due to their age (the voter was eligible to vote, and later returned to the polling place after calling the hotline). Several voters reported being told by poll workers that their provisional ballot would not count.

A larger group of voters reported a general lack of helpfulness when needing assistance — for example, with help locating their correct polling place. Voters also reported feeling a lack of privacy (for example, by announcing party affiliation in a loud voice).

Voting Equipment and Supply Issues

Casting a ballot in North Carolina involves an array of technology that can also vary by county—including ballot marking devices, electronic pollbooks, specialized election software, printers, scanners, and tabulators. A variety of paper ballots and forms are also required to ensure the election process runs smoothly. In jurisdictions where voters mark and/or submit paper ballots, voters are normally instructed to place their marked ballot into a tabulator. When tabulators are out of service, voters are instructed to place ballots into an emergency ballot bin. The bin is unlocked by poll workers once polls close, and all ballots are fed into the tabulator.

Voters in multiple NC counties who sought assistance from Democracy North Carolina during the 2020 primary reported problems with voting machines that delayed and complicated voting. In addition, concerns about the spread of the virus via touch-screen machines will heighten the need for voting equipment sanitization in many counties.

During the 2020 primary election, Democracy North Carolina received 22 reports concerning voting equipment or supplies from voters in the following counties: Bertie, Cumberland, Durham, Forsyth, Halifax, Haywood, Lenoir, Mecklenburg, Northampton, Rowan, and Wake. Several voters reported that the tabulator at their polling place went out of service on Election Day.

These reports included printers being out of service, a lack of Democratic ballots, and a lack of Authorization to Vote forms, which are issued to all voters on Election Day— all which resulted in a pause in voting. In two cases, these delays led to an extension of voting hours at individual polling sites.24 Lastly, voters reported problems with the electronic pollbook, which did not properly sort hyphenated names. This led to voters being inaccurately told they were not on the rolls.

Challenges with Provisional Voting

Provisional ballots are offered to voters when there are questions about a voter’s eligibility to vote. Voters who are not on the voter rolls, show up to the wrong polling place on Election Day, and/or fail to provide needed identification have the option of casting a provisional ballot. Federal law mandates that any voter may request a provisional ballot if they are denied a regular ballot.

Provisional ballots are kept separate from regular ballots. County board of elections staff research the issues surrounding each provisional ballot and provide findings to board members, who decide if the ballot will be counted. Election results are not finalized until all provisional ballots that are eligible have been included in the total count.

During the 2020 primary election, Democracy North Carolina received 19 reports concerning provisional ballot issues in the following counties: Alamance, Buncombe, Chatham, Durham, Forsyth, Guilford, Halifax, Johnston, Mecklenburg, Nash, Orange, and Wake. The majority of these incidents were in regards to out-of-precinct voters who were not offered provisional ballots.

As in past elections, incident reports conclude that provisional ballots are not consistently offered to voters. This is especially the case for out-of-precinct voters, who present to vote at a polling place within their county but in the wrong precinct on Election Day. These voters should always be offered the option to cast a provisional ballot.

However, voters who contacted the hotline consistently reported that they were only given the option of going to their correct polling place. Voters additionally reported being told by poll workers that their provisional ballot would not count. Others reported not receiving any explanation of why they were given a provisional ballot, how the process worked, and how they could find out if their ballot was counted.

Voter Intimidation

Federal and state law prohibits individuals from intimidating, threatening, or coercing an individual in an attempt to interfere with their ability to vote. Examples of voter intimidation include attempts to scare voters away from polling places, aggressively questioning voters about their qualification to vote, and spreading false information about voting requirements or election dates. While rare, voter intimidation continues to pose a serious threat to accessing the ballot.

During the 2020 primary election, Democracy North Carolina received 6 reports concerning voter intimidation in the following counties: Buncombe, Chatham, Chowan, Durham, and Wake. Several callers reported an incident that occurred on Saturday, February 15 in Chatham County. A group of demonstrators gathered to protest an event held in the Chatham County Agriculture & Conference Center, where an early voting site was also taking place. Demonstrators displayed flags supporting the Confederacy and the League of the South (designated a violent hate group by Southern Poverty Law Center) and reportedly yelled slurs— in the same area voters had to traverse to access the designated polling place for early voting. Due to the single-road entrance to the complex, it was impossible for potential voters to avoid seeing these racially intimidating symbols as they entered the early voting complex and polling location. Some potential voters apparently left the area rather than park their cars. Some of the demonstrators were located directly in front of the entrance to the polling location.

Section III: Solutions to Increase Voter Access

With this report, Democracy North Carolina provides timely, fact-based recommendations for protecting voters and expanding voting access amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The current public health crisis posed by COVID-19 will undoubtedly change our upcoming elections. Voters and elections administrators face considerable uncertainty. However, it is likely that the perennial barriers to participation in our elections will be amplified by COVID-19. As counties face resource and budget shortfalls, boards of elections will have to carefully allocate staff and resources in order to ensure that elections run smoothly. Shortly prior to publication, North Carolina enacted legislation that, among other measures, provided over $20 million in state and federal funds for election administration. Even with this necessary support, administrators face increased need from both the anticipated high turnout and the pandemic context. The solutions below seek to alleviate barriers to voting during a typical election and the new challenges posed by COVID-19 and can be addressed by various stakeholders engaged in shaping our election administration.

Machines and Supplies

The North Carolina State Board of Elections (NCSBE) must ensure that there are proper processes and procedures in place to safeguard against issues that may arise due to the high volume of voters for the 2020 General Election, including:

- County boards of elections should test tabulators and voting machines to ensure that they are properly functioning in advance of Election Day;

- County boards of elections should complete an incident report every time a machine malfunctions;25 and

- The State Board of Elections should provide guidelines for where the incident reports are sent and for their comprehensive review to identify any persistent issues and/or patterns.

Additionally, for counties that utilize touch-screen voting machines, it is essential that elections officials mitigate the spread of COVID-19 by increased sanitization measures and offering single-use styluses for voters.

Curbside Voting

Voters often experience difficulties with curbside voting.26 Given the high likelihood that curbside voting will dramatically increase due to COVID-19, it is essential that the NCSBE provide guidance to county boards of elections to ensure that this method of voting remains accessible. This support should consider both the operational needs of high-volume curbside voting and the particular needs of voters with disabilities; NCSBE should consult with disability rights organizations to understand frequent challenges regarding accessibility. Additionally, election judges must ensure curbside voting is monitored at all times and that a designated poll worker is assigned to assist curbside voters. While instructions to election judges include instructions for setting up and running curbside, there is no standardized oversight to ensure compliance with this requirement.27 It is essential that guidance is partnered with sufficient oversight to ensure that curbside voting is both effectively planned and implemented.

North Carolina State Board of Elections Website

Many voters rely on the NCSBE website (ncsbe.gov) to locate important information about how to register to vote or cast their ballot. It is essential that the website be able to handle high-traffic during the upcoming General Election, particularly the voter lookup tool and the polling place locator. The NCSBE is currently preparing a new website; when that site is ready, the agency should utilize performance and load testing to help prevent crashes during early voting and on Election Day. In addition, there are several opportunities to improve voter access by updating the site with multi-lingual materials, prominently displaying voting locations and hours, and ensuring that the recently authorized absentee ballot request portal meets usability and accessibility standards.

Provisional Ballots

The NCSBE must ensure that poll workers consistently offer out-of-precinct voters the option to cast a provisional ballot or to go to their correct precinct. The NCSBE should issue guidance to the counties to ensure that poll workers should be consistently and adequately monitored to ensure that they are offering both options. Additionally, there should be repercussions for elections staff who do not offer both options. Finally, the NCSBE should issue guidance that counties require poll workers to provide the correct polling place name and address to voters who are in the wrong precinct.

Poll Workers

Poll workers are responsible for assisting voters through the voting process, helping to ensure that every voter is able to cast a ballot. Poll workers must help provide a positive voting experience while protecting voters’ rights. However, oftentimes, poll workers fall short of their mission.

We recommend that the NCSBE develop a “Code of Conduct” for North Carolina poll workers, similar to the one developed in the 2016 General Election for polling place observers and outside monitors. The code of conduct should stress the importance of (1) courtesy, respect, and sensitivity toward all voters regardless of age, race, language, gender, and ability; (2) clear communication; (3) efficiency and convenience; (4) basic knowledge of NC election law and administrative guidance; and (5) commitment to ensuring that all eligible voters are able to cast ballots. Failure to abide by this code should be a cause for dismissal.

Additionally, the NCSBE must address the potential for poll worker shortages. As the average age of poll workers across North Carolina is 70 years old,28 it is imperative that adequate election staffing is in place prior to the General Election to guard against precinct consolidation. Precinct consolidation could lead to multiple issues, including congestion in curbside voting, inability for voters to engage in social distancing, and long lines. Elections administrators and the General Assembly should:

- Assess current barriers to poll worker service and meet with interested stakeholders to develop shared solutions;

- Increase and expand state and county efforts to recruit younger, more diverse, culturally competent, and tech-savvy poll workers.

- State and county boards of elections should partner with community groups, like those who participated in prior Election Protection work, who are deeply invested in the intricacies of the voting process to craft recruitment initiatives;

- State and county election officials should work together to provide a clearer pathway to becoming a poll worker for unaffiliated voters. Currently, each county BOE handles requests to become a poll worker differently: some refer volunteers to their local political party, while others have an online sign-up process;

- Make Election Day a holiday in order to bolster poll worker recruitment for persons who would otherwise be working; and

- Recruitment flexibility across precincts and counties should be put in place, at least for the duration of the 2020 General Election.

Voter Registration

North Carolina now has online voter registration (OVR) through the NC Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) website. This is an excellent new option for voters but is only available to those with a driver’s license or other DMV-issued ID. Expanding the platform’s availability should be a priority— the system allows voters to comply with social distancing guidance and also can help make up for the dramatic decrease in in-person voter registration activities. Additionally, robust, multi-lingual voter education about the existing OVR platform can increase the public’s awareness and the platform’s use.

Voters frequently have questions about their voter registration status. The NCSBE should take the following steps to address these common voter questions and issues:

- Add information to the state website explaining the denied and removed voter statuses and clear information about how to register to vote;

- Provide information on the state’s website for inactive voters, noting where they should present to vote, what ID they should bring, and how voters can update their status from “inactive” to “active;”

- Develop a method to report inaccuracies with inactive status stemming from list maintenance; and

- Require DMV staff to inform voters who are registering to vote or updating registration after the voter registration deadline that they must register in-person at an early voting site to vote in the upcoming election.

Polling Place Accessibility and Efficiency

Many voters are familiar with the frustration of waiting in long lines in order to vote and COVID-19 could increase issues at polling locations if there are poll worker shortages and a decrease in voting options. To help address these issues, early voting sites and Election Day polling places with high traffic during certain times of day, such as schools, should coordinate with building staff ahead of time to make a plan for reducing parking congestion. County boards of elections should identify and secure alternate parking options for voters within close proximity to the polling place ahead of time, taking the distance required to walk from parking area to voting area into consideration when deciding on the site location. Additionally, the NCSBE should establish minimum standards for signage, as currently no signs are required. And finally, legislators should consider making Election Day a statewide holiday, which would free up sites and make parking and curbside voting significantly easier.

Absentee Ballots

As North Carolina election officials prepare for a projected substantial increase in absentee-by-mail voting, many of the absentee-by-mail voters seeking assistance from Democracy NC during the 2020 primary reported: (1) lack of clarity on how to request a ballot and who could assist them with it, (2) lack of equipment needed to print a request, and (3) failure to receive a ballot, forcing them to vote in-person or miss the election altogether.

It is essential that barriers to voting an absentee ballot by mail are reduced:

- Create of an online portal for requesting absentee ballots;

- Reduce of the two witness and notary requirement;

- Create of a uniform system for tracking the status of absentee ballots, tying to SSN or ID number to protect voter privacy);

- Simplify the application: the current application is 857 words in 10 point font;

- Mandate that each county provide MAT teams to assist voters in the absentee ballot process and require counties to document MAT requests and the date/time they are filled; and

- Offer adequate voter education in multiple languages on how to vote by mail with an absentee ballot.

Voter Intimidation

Although there were few reports of voter intimidation during the 2020 Primary Election, one instance of reported voter intimidation at a polling location during the 2020 primary (see above regarding the presence of groups waving Confederate flags at an early voting location in Pittsboro) was particularly concerning. Voter intimidation should be a high priority concern because of incidents in previous election cycles, the intensity of the climate and discourse surrounding this year’s election, and the damaging effects of any single intimidation incident. NCSBE and county boards of elections should begin the process for preventing and responding to voter intimidation incidents by taking the following steps:

- Participation in discussion with voting rights and racial justice organizations to formulate proactive plans to address the issue of voter intimidation;

- Strengthen and clarify statewide guidance, training procedures, and other ongoing support needs;

- Centralize and publish communication regarding resources for voters and the public who are concerned about voter intimidation and protecting the fundamental right to vote; and

- Issue an updated formal guidance memo on impermissible conduct at the polls by challengers, poll watchers, and other persons coming to voting sites for reasons other than voting, in North Carolina elections.29

Running elections is no small task. Elections administrators and various stakeholders must consider how to best ensure a safe and secure voting experience for all voters for the upcoming high-turnout General Election in 2020. Changes in our elections administration must take into account the historical and current state of electoral participation and the barriers that voters face, particularly in light of complications posed by COVID-19. The challenges that 2020 present also create opportunities for North Carolina to advance and to lead by example, putting in place processes and structures that help voters and removing barriers that do not, while protecting voters’ health and safety.

Appendix A | Voter Hotline Call Types

General Info: requests for polling place location and hours of operation, questions about election rules, assistance with finding voter registration record, questions about ID needed to vote or register to vote.

Registration: questions about voter registration status (particularly “inactive” status), confusion regarding why a voter was removed from voter registration record or why their voter registration was denied.

Absentee Voting: inquiries about witness requirements, help completing absentee ballot, request for absentee ballot form, reports that absentee ballot requested but not received, reports that absentee ballot mailed to wrong place.

Curbside Voting: reports of curbside voting being unavailable, inaccessible, and/or unattended.

Poll Worker: reports of poll workers making inappropriate comments to voters, providing voters with inaccurate information, being confrontational or unhelpful.

Long Lines: reports of long lines (30 minutes or more) at a polling place.

Voting Equipment & Materials: reports of voting machines or tabulators being broken or unavailable, polling places running out of necessary forms.

Intimidation: reports of voters feeling intimidated during the voting process (by poll workers, campaigners or other voters) or witnessing purposeful disinformation.

Provisional: reports of voters in the correct county but incorrect precinct not being offered a provisional ballot, confusion regarding voting a provisional ballot.

DMV-related: reports of issues with voter registration stemming from registration at DMV.

Appendix B | Narratives

Voting equipment and supply issues

Around 7:30 a.m. on Election Day, K.P. called the Election Protection hotline and reported a broken printer at the Snakebite precinct in Bertie County. She and other voters were turned away and wrongly informed that polls closed at 7 p.m. (30 minutes earlier than the actual closing time). Democracy North Carolina quickly deployed a Vote Protector to the site and informed the State Board of Elections of the interruption. Later that evening, the State Board of Elections mandated a 30-minute extension for Snakebite, pursuant to General Statute 163-166.01. The Hours for Voting statute states that the State Board of Elections may extend precinct operation hours to mirror the period of any interruption longer than 15 minutes. Around 7:30 p.m. K.P. and other voters arrived at Snakebite and were able to cast their ballots.

At the Miller Park Recreation Center precinct in Forsyth County, long lines formed due to an insufficient supply of Democratic ballots. The Election Protection hotline received a call from a voter who successfully voted but saw others turned away. The stoppage persisted for 40 minutes. The Forsyth county board of elections suggested an hour extension, 20 minutes more than the period of the interruption, to account for transit to polls. However, the State Board of Elections mandated an extension equal to the 40 minutes the polling place went without Democratic ballots.

In a particularly strange case, a select few voters at the Little Creek Recreation Center precinct in Forsyth County had an additional, confusing step in their sign-in process. The Election Protection hotline received two calls the morning of Election Day, reporting a problem with Authorization to Vote (ATV) forms for voters with last names following ‘Williams.’ In one case, a voter was turned away. In another, a voter was told she could cast a provisional ballot, but she decided against it and contacted the Forsyth county board of elections office instead. Democracy North Carolina sent a Vote Protector to the polling place to get more information. The Vote Protector confirmed that the electronic pollbooks ended with Williams, and affected voters were being directed to the Help Desk to fill out ATV forms manually. We are unsure if the two voters we learned of via the hotline were able to vote.

Curbside Voting

My job [as a poll monitor] quickly became curbside voting coordinator, as I had to park handicapped cards wherever I could, then keep track of which order they should be served. At least 3 curbside voters left due to long waits, saying they would try again on election day. – J.D., Poll Monitor stationed at South Buncombe Library (Buncombe County) on 2/29/20.

Polling Place Accessibility & Efficiency

B.D. reported arriving at the North Asheville Public Library just after noon on the last day of early voting: Saturday, February 29. When he arrived with his fellow UNC Asheville students, he was stopped by a poll worker and told to remain outside. After 15 minutes of waiting, the students decided to defy the rule and enter the building. After making his way to the front of the line, he identified himself and asked to register to vote. He reported that one poll worker exclaimed “I am done, I’m not registering anyone else today,” and walked away from her post. Another poll worker sighed and said it would only be a few more minutes. After waiting over an hour, B.D. gave up and left without casting a ballot.

Poll Worker Conduct

N.S. described herself as a young black student who attends NC State University. She reported voting at the NC State’s Talley Student Union in Wake County at approximately 8 AM on Saturday, February 29th. After giving her information to a poll worker named P.M., she moved down the line to collect her ballot from an older white woman. Before this woman handed N.S. her ballot, she leaned in and said “You know, there are racists on both sides of the ballot.” N.S. did not respond. After voting her ballot, she exited the building and was approached by a Democracy NC Vote Protector (M.W.) who was stationed outside the early voting site. M.W. called the hotline to report the incident.”